Alhambra Tiles

The Alhambra tiles

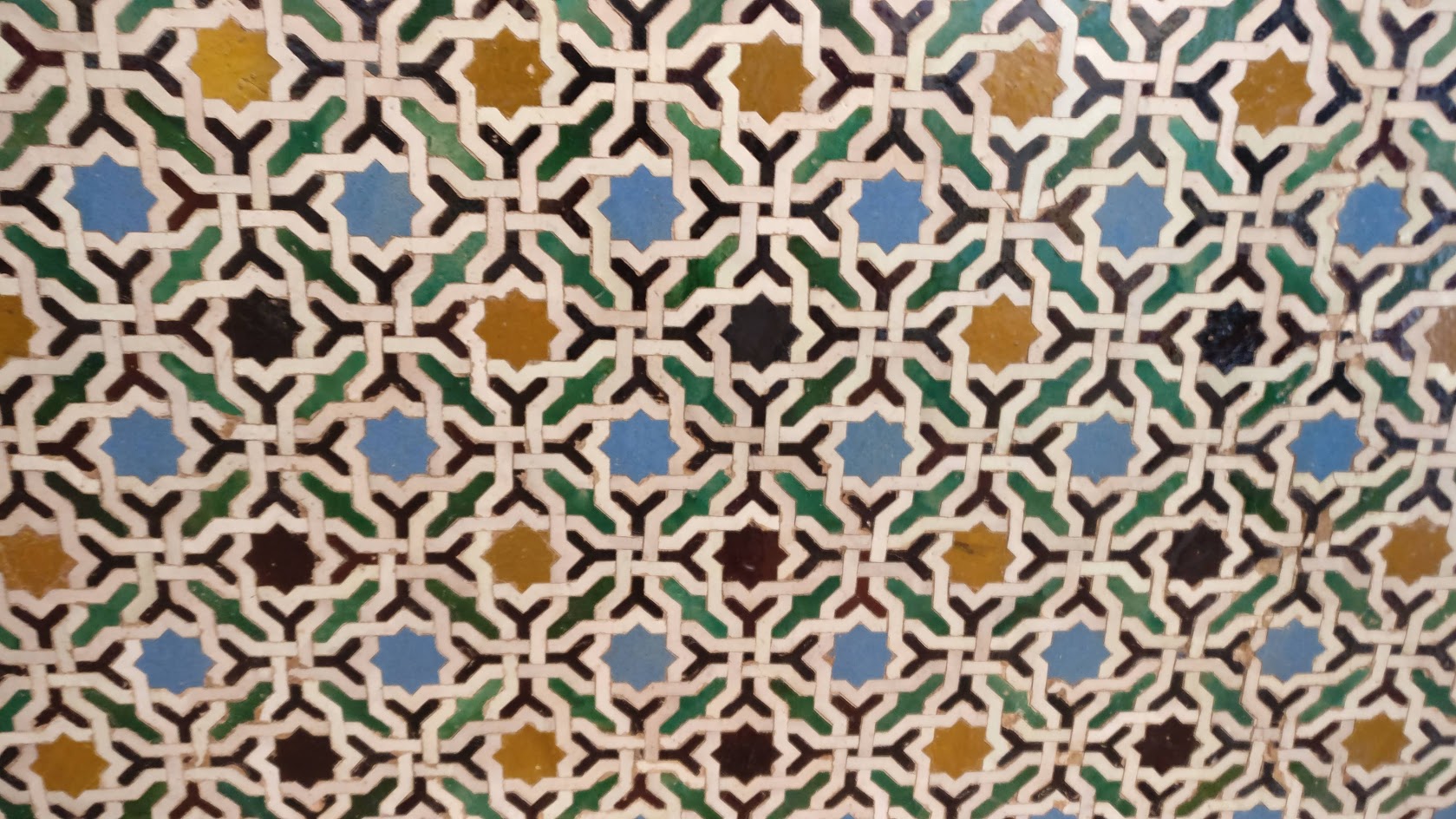

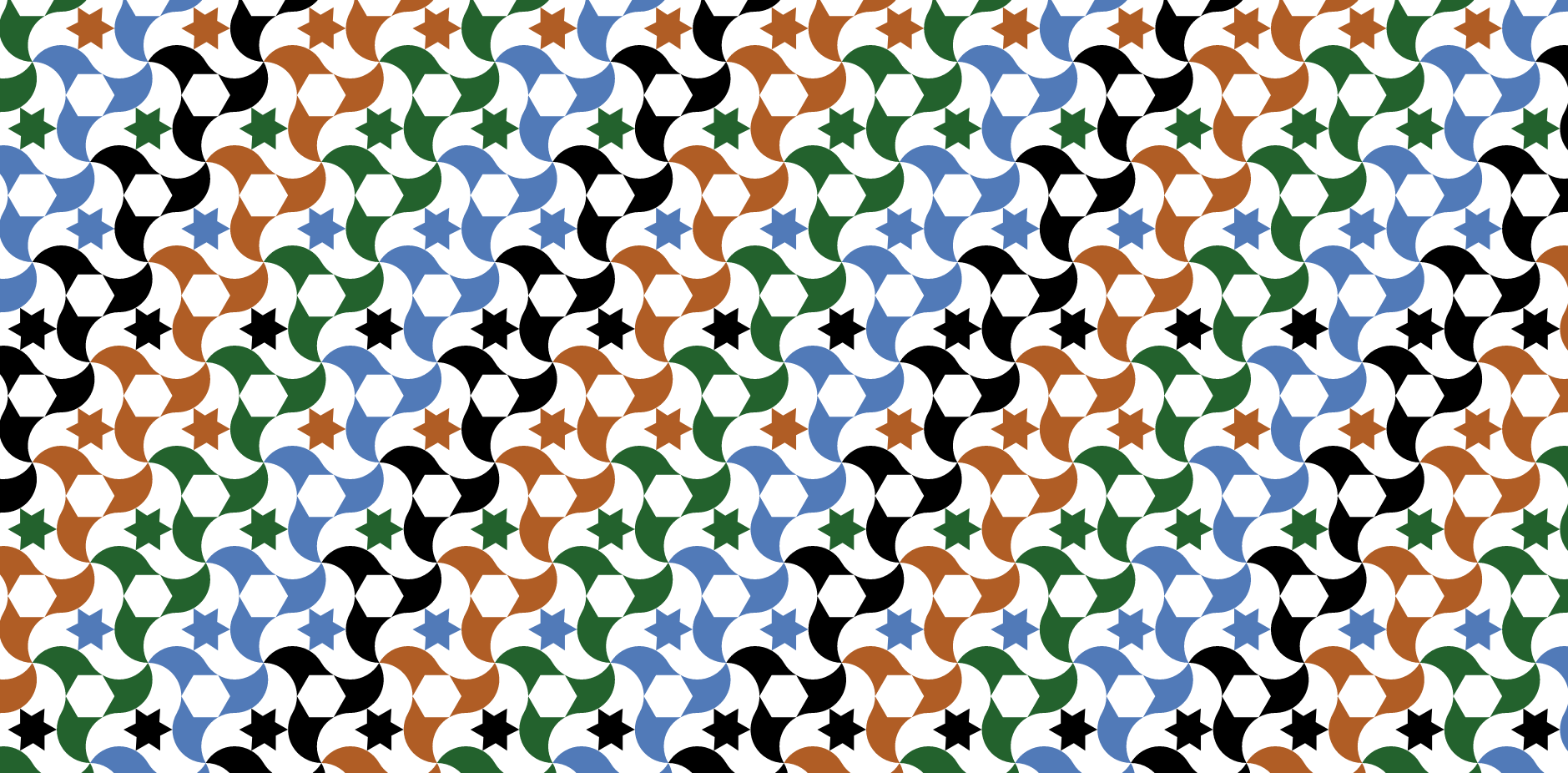

A few years ago I visited the Alhambra in Granada, Spain. I was fascinated by the beautiful tiles, by their geometric patterns and repetitive colours. Here is one with overlapping white ribbons wrapped around blue, black and orange octogons:

This one is formed by repeated rectangular shapes, darkly coloured in one direction, white in the orthogonal direction:

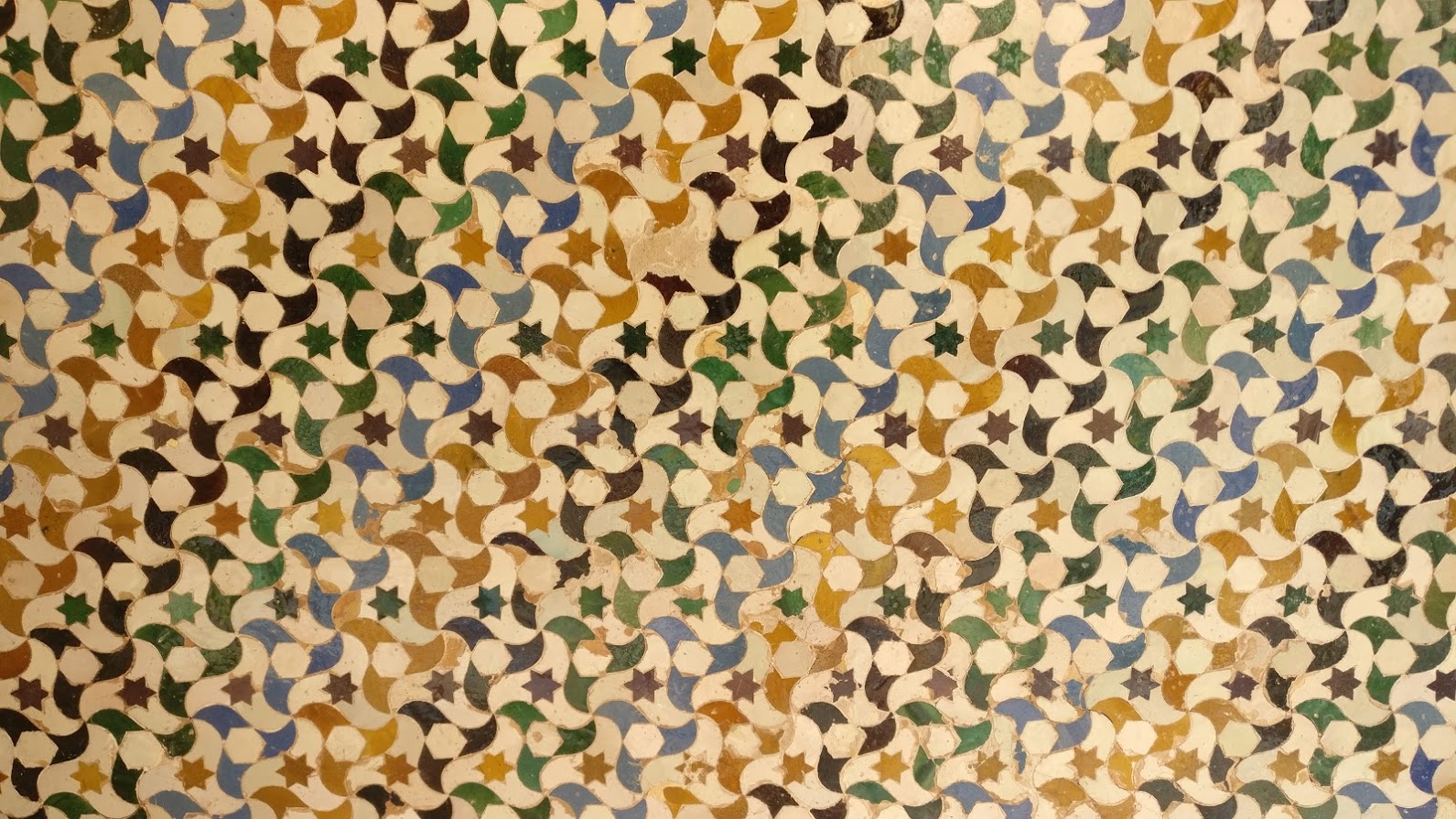

And this one with its stars and wings is known as the Nasrid little bird:

I recently started learning Javascript, and decided to use the Canvas API to draw the little bird pattern above. You can interact with the pattern on desktop by using the mouse to move it around and to zoom in and out. It also works on mobile (use Chrome instead of Firefox to be able to move around). The source code is on Github. Note that halfway through I switched from Javascript to Typescript.

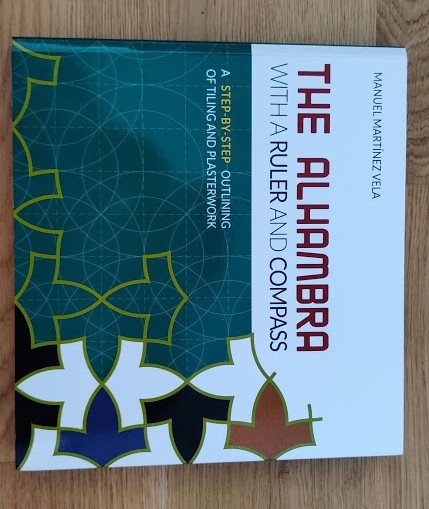

I used the Nasrid little bird pattern above. This is the name given to it by a wonderful book The Alhambra with a ruler and compass by Manuel Martínes Vela:

As the name suggests, The Alhambra with a ruler and compass explains how the patterns can be drawn by hand using only a ruler and a compass. Each pattern is shown on a grid, similar to the one on the cover. From the pattern and the grid you can infer the length, curvature and relative position of each line segment.

It is not too hard to render a static image of the pattern. To make it more interesting, I wanted to be able to move the pattern around, and zoom in and out. The pattern has no boundary, so I wanted to be able to move infinitely far in any direction.

In the rest of this post, I’ll give an overview of the Typescript code used to define the pattern. And I’ll describe the algorithm that’s used to give the impression of an infinite 2D plane.

Drawing the little bird pattern

I decided on a completely stateless approach. The only state is a 2D translation vector and a scaling factor (the zoom level). Together these represent the current transformation of the pattern. An event such as click-and-drag changes the transformation and triggers a new rendering of the pattern from scratch.

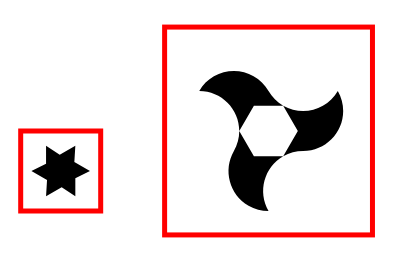

The little bird pattern consists of two units repeated along a 2D lattice, in this case a hexagonal lattice. The first unit is the six-sided star. The other unit consists of three curved triangular wings arranged symmetrically around a white hexagon.

A single unit

The first step is to draw each of the basic units. Here is the code for drawing the star:

const littleBirdStar: Unit = {

draw: function (ctx: CanvasRenderingContext2D) {

const r = Math.sqrt(3) - 1;

ctx.moveTo(r, 0);

ctx.save();

for (let i = 0; i < 6; i++) {

ctx.lineTo(r, 0);

ctx.lineTo(0.5 * r, 0.25 * r);

ctx.rotate(Math.PI / 3);

}

ctx.lineTo(r, 0);

ctx.restore();

},

boundingBox: new Rectangle(new Vector(-1, -1), new Vector(1, 1))

}

In addition to specifying how to draw the star (the draw function), we have to define a rectangular bounding box that contains the star. The bounding box is used later to determine if a translated star is still inside the canvas. We’ll know that it’s outside the canvas if the bounding box and the canvas don’t overlap. The bounding boxes are shown in red in the image above.

The draw function and bounding box for the wings is specified in a similar way.

Covering the canvas

The next step is to cover the canvas with stars. For this we need to know the location of the canvas, and the transformation (shift and scale) that should be applied to the star before drawing it. Note that the bounding box given above has a width and height of only 2 pixels, so we will need a transformation with a scale much larger than 1 to be able to see it.

To incorporate transformations, I created the following Drawable type:

type Drawable = (ctx: CanvasRenderingContext2D, transformation: Transformation) => void;

An object of type Drawable knows how to draw itself on a canvas after applying a given transformation to it. Because the transformation will vary while the canvas remains fixed, I decide to pass the transformation as a parameter to the callable Drawable object, while the canvas is passed to the constructor of a Drawable object (see below).

For covering the canvas with our star, we can create a Drawable like this:

const starTilingReference = createTiling(

littleBirdStar,

new Basis(new Vector(2 * Math.sqrt(3), 0), new Vector(0, 12)),

canvas

);

The object starTilingReference is a Drawable which repeats the star along the lattice spanned by the two Basis vectors. It uses the canvas parameter to avoid drawing the star at lattice points that lie too far outside the canvas.

Before drawing the stars, we have to fill them with an appropriate colour, in this case black:

let starTiling = withFill(starTilingReference, "black");

...

function withFill(draw: Drawable, fillStyle?: string): Drawable {

return (ctx, transformation) => {

ctx.beginPath();

draw(ctx, transformation);

if (fillStyle) {

ctx.fillStyle = fillStyle;

}

ctx.fill();

}

}

The function withFill is one of several higher-order functions that map a Drawable to another Drawable.

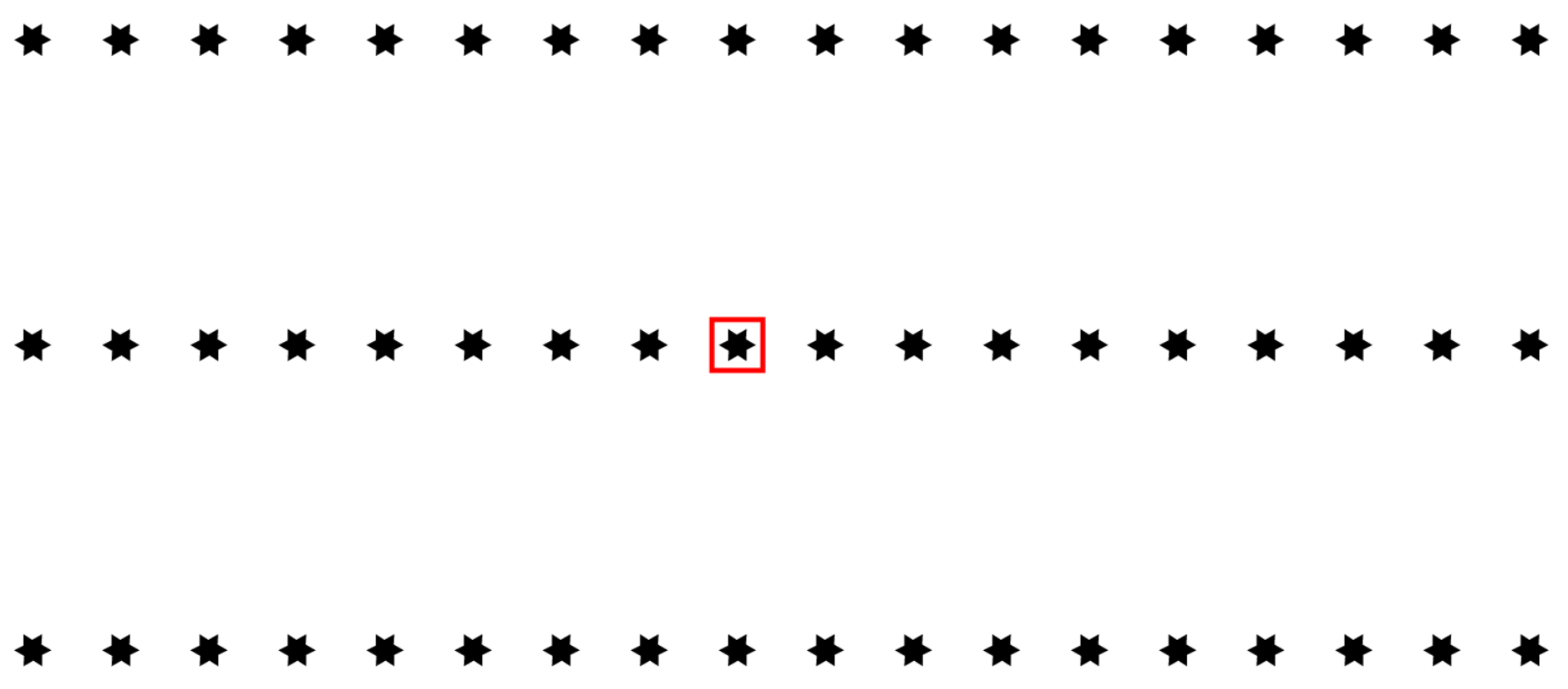

Here are the resulting black stars:

The red bounding box indicates the unit that is closest to the center of the canvas.

This is a rectangular rather than a hexogonal lattice, because we’re still missing the other stars (the ones that are not black).

Adding colours

To add the other stars, we shift the above lattice using another higher-order function from Drawable to Drawable:

function withModifyTransformation(

draw: Drawable,

modifyTransformation: (t: Transformation) => Transformation

): Drawable {

return (ctx, transformation) => draw(ctx, modifyTransformation(transformation));

}

This produces three additional tilings. These four tilings are combined to form a single Drawable using yet another higher-order function:

function joinDrawables(drawables: Drawable[]): Drawable {

return (ctx, transformation) => {

for (const drawable of drawables) {

drawable(ctx, transformation);

}

}

}

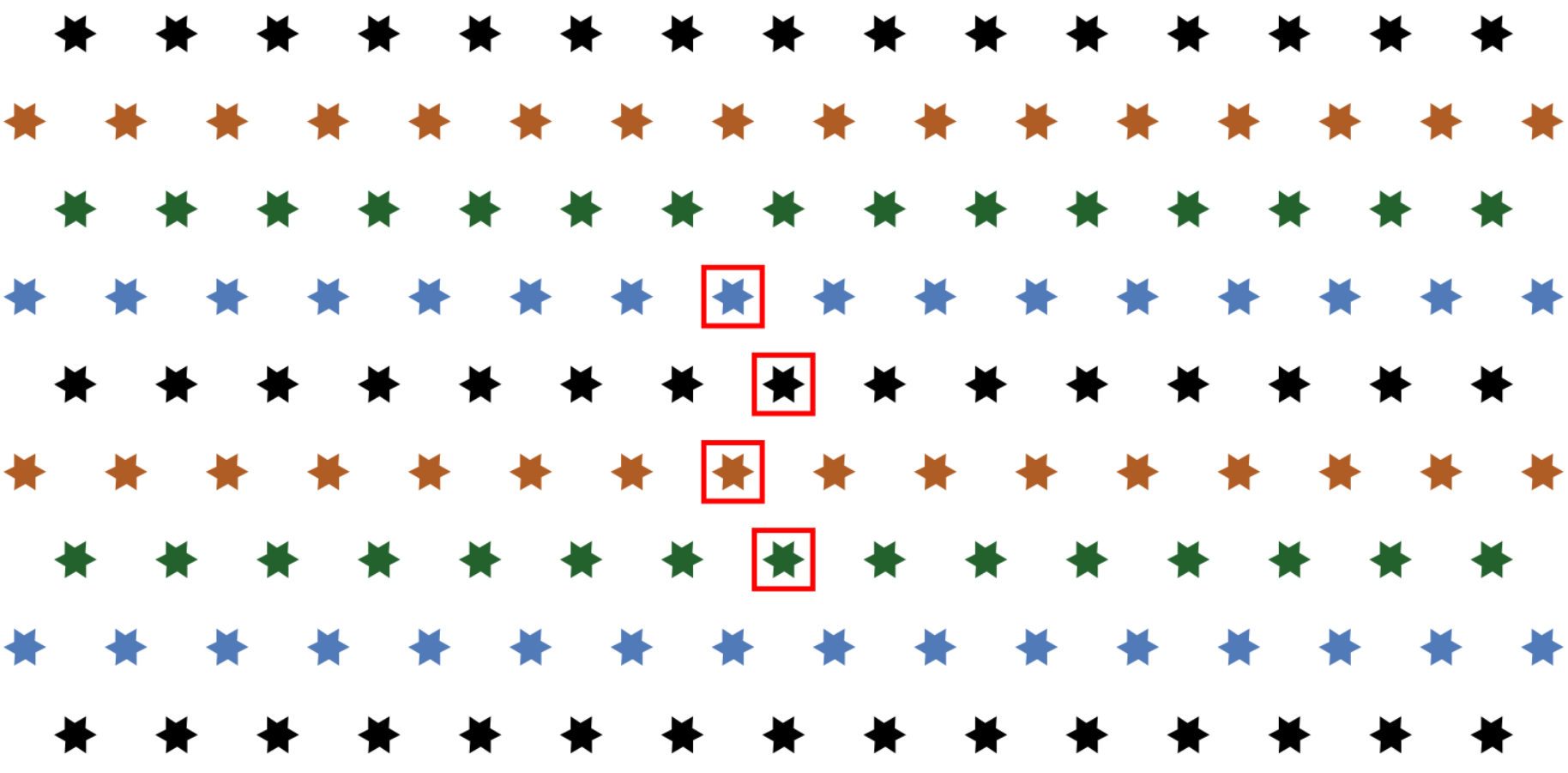

Here are all the stars for the final pattern:

The wings

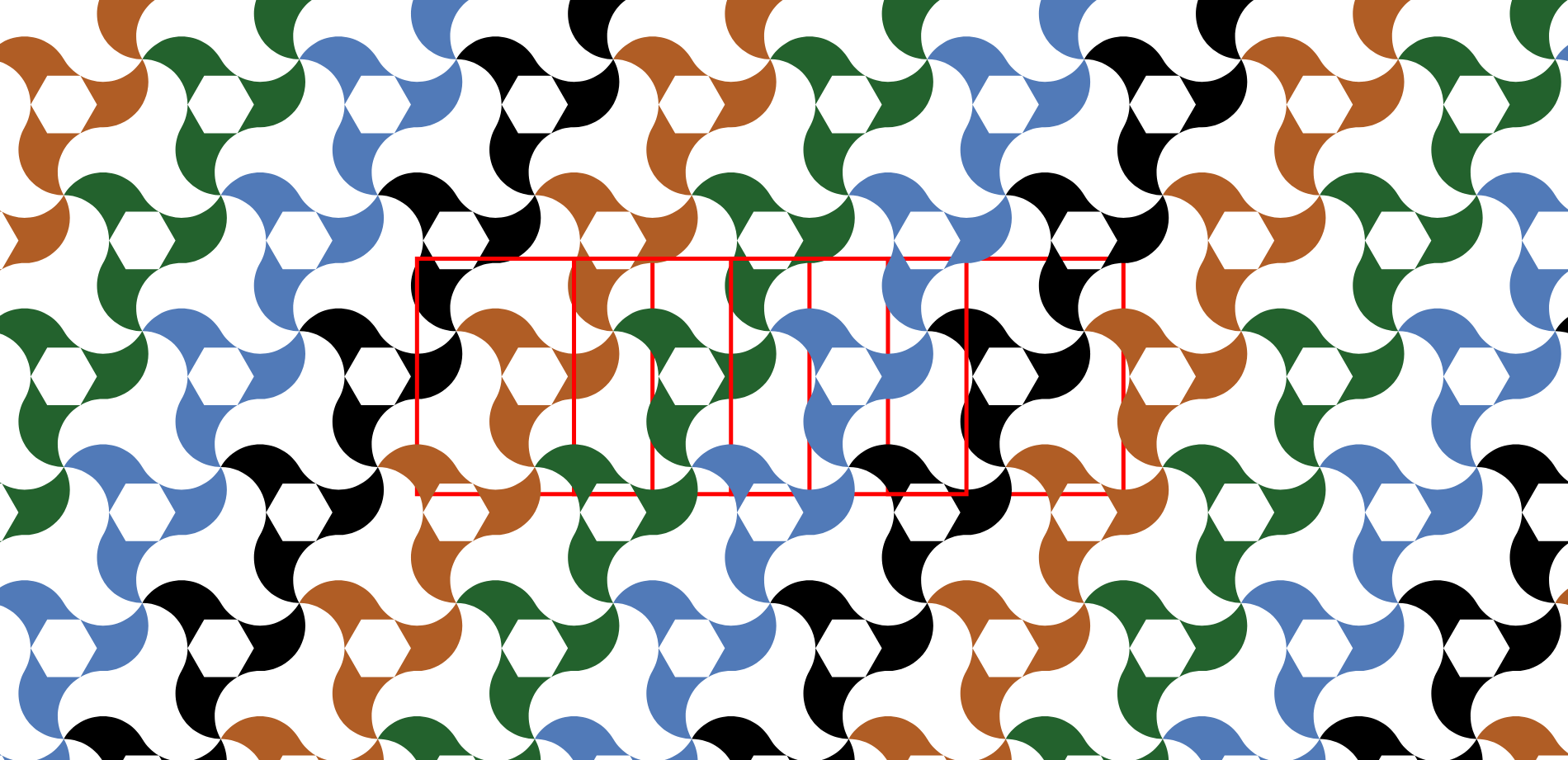

Repeating all the above steps using the wings instead of the stars gives:

The final pattern

Combining the stars and the wings yields the final pattern:

Additional patterns

It should not be too hard to add additional patterns. All the code used to define the little bird pattern is in the same .ts file with less than 90 lines. Only this file would need to be modified to create another pattern.

An algorithm for filling the canvas

Earlier we covered the entire canvas with a single star using this code snippet:

const starTilingReference = createTiling(

littleBirdStar,

new Basis(new Vector(2 * Math.sqrt(3), 0), new Vector(0, 12)),

canvas

);

Implementing the createTiling function was the most challenging part of this project. More precisely, createTiling calls a function generateCovering, which contains the tricky part. Here’s its signature:

function generateCovering(

boundingBox: Rectangle, basis: Basis, canvas: Rectangle

): Array<Vector>

Both the bounding box and basis have been transformed to the coordinate system of the canvas before calling this function.

The basis defines a discrete 2D lattice which acts on the bounding box via translation. The goal of the generateCovering function is to find the bounding boxes that overlap with the canvas.

This is important, because these overlapping bounding boxes are exactly the ones for which we should draw the unit (eg. the star).

There were two parts to this task: coming up with an algorithm, and proving that it’s correct. I’ll leave out the proof, but should note that trying to prove correctness was essential in understanding why earlier versions of the algorithm occasionally failed to find all the overlapping bounding boxes.

Definitions

We are given a bounding box, a canvas, and two basis vectors $\mathbf{v}, \mathbf{w} \in \mathbb{R}^2$, where $\mathbb{R}^2$ is an additive group that acts on the bounding box via translation. The basis vectors span a discrete subgroup of $\mathbb{R}^2$, the 2D lattice $\{a\mathbf{v} + b\mathbf{w} \, | \, a, b \in \mathbb{Z}\}$. Points on the lattice are described by their integer coefficients in the basis. For example, the lattice point $(a, b) \in \mathbb{Z}^2$ corresponds to the translation $a\mathbf{v} + b\mathbf{w} \in \mathbb{R}^2$.

To each point in the lattice we associate the translated bounding box with its center at that lattice point. The lattice point $(0, 0)$ is associated to the bounding box that was part of the input to the algorithm.

We’d like to assume that this input bounding box or one of its neighbours overlaps with the canvas. But because the user can move the pattern arbitrarily far in any direction, the input bounding box might be very far away from the canvas. Therefore the first step is to find the point in the lattice that is closest to the center of the canvas. The bounding box centered at this central lattice point then replaces the input bounding box as the reference corresponding to lattice point $(0, 0)$.

The task is now to find the set of lattice coefficients $(a_1, b_1), \ldots, (a_n, b_n)$ such that the corresponding bounding boxes are exactly the ones that overlap with the canvas.

Properties of the set of lattice coefficients

Before describing the algorithm to find the set of lattice coefficients, we will identify two properties of the set that the algorithm will rely on. In addition, we’ll specify assumptions that the bounding box and canvas need to satisfy for these two properties to hold.

To gain intuition, consider a simple discrete lattice with basis vectors $(1, 0)$ and $(0, 1)$. Then the set of coefficients that we’re looking for form an unrotated (i.e. axis-aligned) rectangle: $$\{(a, b) \in \mathbb{Z}^2 \, | \, k \leq a \leq l, m \leq b \leq n \}$$ for some $k, l, m, n \in \mathbb{Z}$.

More generally, for orthogonal basis vectors the set of coefficients will look like a rotated rectangle, and for arbitrary basis vectors it will be a parallelogram.

Intuitively then, the set is connected and convex.

The natural definition of a convex subset of $\mathbb{Z}^2$ is probably that it’s of the form $\mathbb{Z}^2 \cap U$ where $U \subset \mathbb{R}^2$ is convex. But this is stronger than what we’ll need, so we’ll use this weaker definition: the finite set $S \subset \mathbb{Z}^2$ is convex if its intersection with any row or column is connected. I.e. for any $n \in \mathbb{Z}$ the intersection $\{(a, n) \in S \, | \, a \in \mathbb{Z} \}$ is of the form $\{a \, | \, k \leq a \leq l\}$ for some $k, l \in \mathbb{Z}^2$, and similarly for intersections with columns. For example, the set $\{(1, 0), (2, 0), (3, 0)\}$ is convex, but $\{(1, 0), (2, 0), (4, 0)\}$ is not. Note that this definition includes T-shaped sets which are not convex according to the natural definition.

According to our weaker definition, the set $\{(0, 0), (5, 1)\}$ would also be convex. But this seems unlikely to correspond to all overlapping bounding boxes (for example we might expect $(2, 0)$ to also be in the set). It contradicts our expectation that the set should be connected. To define connectedness, we first define the neighbours of a point as all its eight neighbours, i.e. including the diagonals. A set is then considered to be connected if there’s a sequence of pairwise neighbours between any two points in the set.

We would now like to claim that the set of coefficients of overlapping bounding boxes is always a connected convex set. Surprisingly, this is not true! For example, the set $\{(0, 0), (5, 1)\}$ given above can occur. It turns out that this can only happen if the bounding box or canvas is very elongated, i.e. the aspect ratio is very different from 1.

We could rescue our claim by relaxing the definition of what it means to be neighbours, with the amount of relaxation depending on the aspect ratios of the bounding box and canvas. But it’s simpler to just replace both bounding box and canvas by the smallest squares that contain them. For example, if the width of the canvas is greater than its height, replace it with a canvas with the same width but a larger height to turn it into a square, and the center at the same position. For a canvas with aspect ratio r, this would slow down the algorithm by a factor of r, but at least it allows us to prove that our algorithm always works.

So to summarise, if we assume that the bounding box and canvas are both squares, then the set of coefficients of overlapping bounding boxes will always be connected and convex.

The algorithm

The algorithm for finding the set of lattice coefficients corresponding to bounding boxes that overlap with the canvas is as follows:

- Initialise the set of coefficients to just the origin: $\{(0, 0)\}$.

- Find the smallest $a_0$ and largest $b_0$ such that all the points from $(a_0, 0)$ to $(b_0, 0)$ are in the set by searching to the left and right from the origin.

- Next, find the smallest $a_1$ and largest $b_1$ such that all the points from $(a_1, 1)$ to $(b_1, 1)$ are in the set. Start by setting $a_1 = a_0 - 1$, do a linear search to the left and then to the right if necessary. Similar for $b_1$.

- Continue like this until we find a row with no points in the set.

- Repeat in the negative y-direction.

This gives the entire set. The reason that we have to start searching at $(a_0 - 1, 1)$ for example instead of $(a_0, 1)$ is because a given point has eight neighbours, not four. In addition, it could be that the origin $(0, 0)$ is not in the set. But if the set is not empty, one of the eight neighbours of the origin will be in the set.

Time complexity

As we zoom out, the number of bounding boxes inside the canvas increases, along with the time needed to update the canvas. The time to update the canvas is partly taken up by running the algorithm above (generateCovering), and partly by drawing the pattern on the canvas (transformDraw). These two parts differ in their time complexity.

The above algorithm only considers bounding boxes that are near the canvas boundary, not ones inside the canvas far from the boundary. Every row of the set of coefficients is represented by its edges, not the entire row. Let $k$ be the ratio between the size (width or height) of the canvas and the size of the bounding box. Then the time needed for finding the coefficients using the above algorithm is linear in $k$. But since the total number of coefficients increases quadratically, the time for drawing the pattern is quadratic in $k$.

I used a profiler at different zoom levels to confirm the linear and quadratic time complexities. When viewing the pattern at its initial zoom level, the two parts take roughly the same amount of time. But as we zoom out the time required to draw the pattern starts to dominate.

This implies that if we wanted to decrease the time needed to update the canvas, we should not focus on optimising the algorithm for finding the lattice coefficients.

Conclusion

Besides the algorithm discussed above, there were a few other interesting aspects to the project:

- It was harder than expected to ensure that we zoom relative to the mouse pointer, i.e. that the point of the pattern at the mouse pointer remains fixed while zooming in and out.

- Another tricky part was finding the coefficients $a$ and $b$ for given $\mathbf{z}$ and basis vectors $\mathbf{v}$ and $\mathbf{w}$ such that $\mathbf{z} = a\mathbf{v} + b\mathbf{w}$. I was familiar with the solution when $\mathbf{v}$ and $\mathbf{w}$ are orthogonal ($a = (\mathbf{z} \cdot \mathbf{v})/(\mathbf{v} \cdot \mathbf{v})$), but not with the non-orthogonal case. This part was necessary for finding the bounding box closest to the canvas center.

This was a fun project for learning some Javascript. Halfway through I switched to Typescript, which made the code easier to read and debug. I used Parcel to automatically update the local page every time I modified a file.

I also enjoyed the process of repeatedly refactoring the code to simplify it and introduce new abstractions. During this process several of the classes that I started with turned into functions, and the only classes that remained were simple ones such as Vector, Basis, Rectangle and Transformation.

My next step would be to add more patterns.